Shut Down Social Media If You Don’t Like Terrorism?

In the aftermath of a violent terrorist attack in Sri Lanka, the government shut down access to social media sites, with widespread implications.

Credit: Flickr

Authors

Area of Study

Tags

This article was originally published at The Washington Post.

In the aftermath of Sunday’s violent terrorist attacks in Sri Lanka, the Sri Lankan government shut down access to social media sites as the investigation into the bombings proceeded. News reports listed Facebook — including its WhatsApp and Instagram platforms — YouTube, Snapchat and Viber as sites the government had banned. According to these reports, the ban will be temporary.

This wasn’t the first time the government had shuttered social media in Sri Lanka, although the previous incident, last April, was in response to violence that the government claimed originated from rumors spread on social media platforms. Nor is Sri Lanka the only country to grapple with concerns over social media-inspired violence: India has blamed WhatsApp in particular for inciting violence.

Governments around the world have begun to scrutinize how perpetrators of violence use social media to publicize their violent actions. A recent and vivid example is the attempt by the alleged assailant in the Christchurch shootings in New Zealand to live-stream his actions.

Taken together, these developments may lead most observers to greet the actions of the Sri Lankan government with a collective shrug, comfortable in the belief that this is simply an effort to deal with negative spillovers from social media platforms. But Sri Lanka’s decision has widespread potential implications, both in the short and long terms. Here’s why.

Social media plays an important role in emergencies

A 2016 Wired Magazine piece described how social media has transformed how people respond to disasters — and rely on these networks to locate loved ones. The way in which social media has transformed key facets of disaster prevention and relief, such as informing people’s decisions to seek out further information about the disaster, has also been the subject of academic research. Turning off social media during crises, therefore, means these potential sources of information are no longer available to those who might need it.

WhatsApp poses a particularly thorny challenge. While governments have blamed the app for spreading misinformation that then leads directly to violence — indeed, this is exactly the justification Sri Lanka’s government gave for blocking access to social media — this is also a chat app that more than 1.5 billon people around the world use monthly to text or make voice or video calls. Shutting off access to a primary means of communication during an emergency situation may leave those searching for friends and loved ones particularly vulnerable.

Would a ban amplify the effects of terrorist attacks?

Social scientists use the phrase “moral hazard” to describe situations in which an automatic reaction to an event that is designed to mitigate the consequences — however well-intentioned it may be — could have the opposite effect. The classic example is insurance: If I buy fire insurance for my house, I may not spend extra money for more costly but safer materials while building the house, thus paradoxically making it more likely that the house will burn down.

Shutting down social media in the aftermath of a terrorist attack may create a similar set of unintended consequences. If terrorists assume that governments are likely to shut down social media platforms after an attack, that might make carrying out such an attack seem that much more appealing to the terrorist group.

Why? Let’s assume that shutting down social media costs harms economic activity in that country — or simply makes the government less popular. Suddenly, a potential attacker might see an added benefit of creating further chaos, via more widespread economic or political disruption.

National bans on social media affect only those without access to VPNs

A national ban on accessing social media is simply that: a ban for accessing social media from within that country. Those with a virtual private network (VPN), however, can easily circumvent such a ban. It is hard to imagine that an organization with the resources to pull off a terrorist attack would not have access to VPNs, as BuzzFeed correspondent Megha Rajagopalan notes:

The end result? A national ban on social media access in a moment of crisis could well leave citizens without information, while perpetrators of violence have no problems communicating.

It’s a slippery slope

More generally, we think of nondemocratic regimes cutting off social media, not democratic ones. What’s the broader impact if democratic regimes begin to ban social media in the aftermath of terrorist attacks?

For starters, nondemocratic regimes probably would seize the opportunity to justify similar actions when it suits them. After all, if democratic regimes are willing to shut off access to these platforms because they pose a threat to national security, who is to argue that nondemocratic regimes are not justified in doing the same thing?

Even within democratic societies, it is worth considering the long-term effect of what it means to cut off access to news — however vulnerable to manipulation and disinformation those news sources may be — in times of crisis. If the justification is that social media platforms can lead to the dissemination of potentially harmful information, is the next argument that it might also be necessary to cut off access to traditional media in the immediate aftermath of a national trauma?

Policymakers have a difficult — but consequential — choice

As stories proliferate about the links between misinformation on social media and violence, the temptation for policymakers to seek quick fixes in moments of crisis will undoubtedly grow, as well. That does not, however, mean that banning access to social media at these moments will reduce the risk of violence.

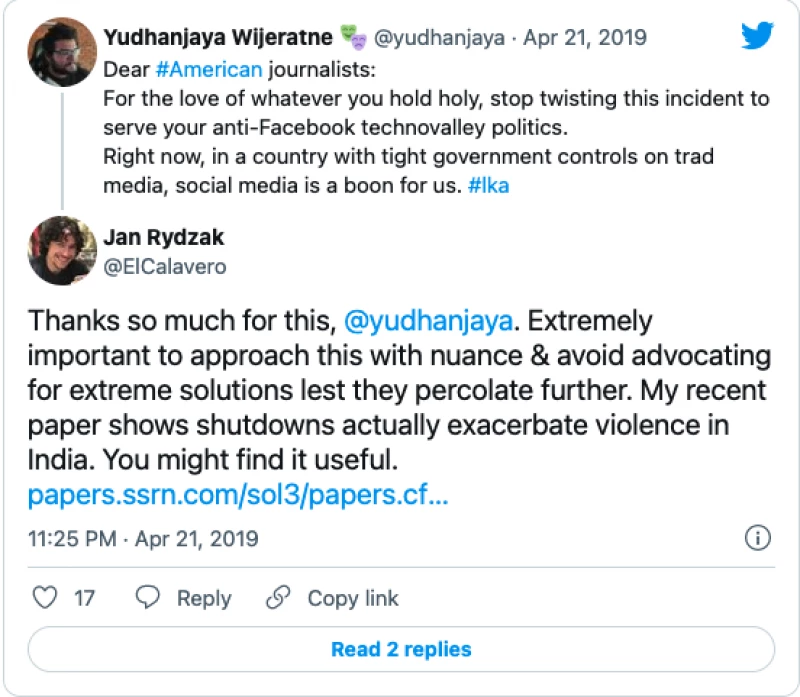

Indeed, we might even worry that being cut off social media could increase the propensity to violence in crisis situations simply because citizens are left without information. New research from Jan Rydzak on network outages in India suggests this may be the case:

Taking this one step further, imagine a future Chernobyl-like event where a government responds to a nuclear accident by shutting down social media in an effort to avoid “panic.” One suspects that such a reaction would not be greeted with a shrug by the larger international community — nor by the families who would lose precious time in reacting to the emergency.

Thanks to Nathaniel Persily for helpful suggestions.