- Home /

- Impact /

- News & Commentary /

- You’re More Likely to Protest if Your Friends Are Protesting, Too

You’re More Likely to Protest if Your Friends Are Protesting, Too

Our research shows protesters are far more connected to each other — via direct and indirect social ties — than are non-protesters.

Credit: Pixabay

Area of Study

Tags

This article is part of CSMaP’s ongoing Research Summary series. We’ll provide quick, digestible versions of our published research articles for peer researchers, journalists, policymakers, and all those interested in the relationship between social media and politics. This week, we wrote about the first large-scale study examining social ties among protesters.

Black Lives Matter protests have swept the globe this month. Demonstrators from Minneapolis — where George Floyd was killed by a police officer on May 25 — to Perth, Australia took to the streets to demand an end to police brutality, structural racism, and other systems of oppression.

These protests are larger in size and scale, and were sustained for longer periods of time, than many other public demonstrations in recent history. They sparked a wave of high-profile resignations across policing, publishing, and many other fields, forced reluctant lawmakers to adopt policy changes, and changed the contours of public opinion on the Black Lives Matter movement. As of this writing, they are still going on in large cities and small towns across the United States.

These protests prompt questions researchers have asked for decades: Why do some people decide to protest while others don’t? How do they make these decisions? And are they influenced by their social ties, as some theories would suggest? The answers remain elusive because protest data is hard to collect and prone to error: It usually involves tracking down and surveying protesters after they’ve protested, which means their responses could be filtered through memories and the judgements of others.

In 2015, our researchers saw an opportunity to overcome these hurdles when more than a million people gathered in Paris’s Place de la République. The crowd was protesting the actions of gunmen who killed 12 people at the offices of Charlie Hebdo, a French satirical magazine accused of publishing racist and Islamophobic content. We collected data from nearly 130 million Twitter users — 764 of whom were geotagged at the site of the protest — to explore the relationship between social networks and protest participation. The dataset provides a snapshot of real-time, observable social ties among protesters and is the first large-scale study to test social theories of protest, which hold that a person’s decision to protest is influenced by others in their social network.

“Are you more likely to show up if your friends show up, and if so, can we get any clue as to why?” said Jonathan Nagler, a professor of politics and co-director of the NYU Center for Social Media and Politics (CSMaP). “And if you don’t show up, will you be the odd one out? Will you have failed to participate in this socially desirable act?”

The answer, according to our findings, is yes: Protesters are far more connected to each other — via direct and indirect social ties — than are non-protesters. In the context of Twitter, you’re more likely to protest if you follow people who are protesting, and follow people who also follow people who are protesting. The results provided evidence for a longstanding theory that the structure of social networks has consequences for protest participation, which previously was impossible to test at scale.

Protesters are far more connected to each other — via direct and indirect social ties — than non-protesters.

Nagler co-authored an award-winning journal article detailing the findings with Jennifer Larson, an associate professor of political science at Vanderbilt University, Jonathan Ronen, a Ph.D. fellow at the Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology, and Joshua Tucker, also an NYU professor of politics and CSMaP co-director.

Here’s how we arrived at these findings: We drew our data from the universe of Twitter users who tweeted during the protest using popular hashtags such as #JeSuisCharlie or #CharlieHebdo. We divided these users into two groups: 764 protesters who were geotagged at the site of the protest, and 764 non-protesters who were geotagged elsewhere in Paris at the time. We then captured the full Twitter network for both groups, measured out to two degrees. In other words, we collected the usernames of those followed by each person in the dataset (their “ties”), and the usernames of those followed by these ties (“ties of ties”). The dataset totaled nearly 130 million Twitter users who were part of these networks.

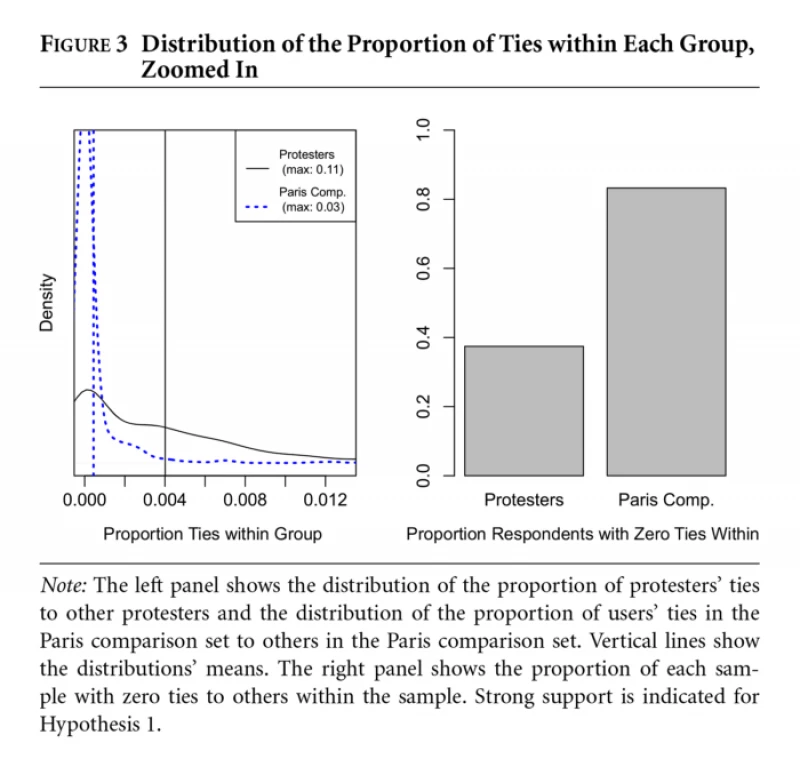

We found protesters have more ties and ties of ties to one another than non-protesters do. This supports the theory that exposure to others in a network is strongest when ties are direct, and still strong when ties are indirect. Protesters also have more “reciprocated ties” (those they follow on Twitter who follow them back) and more “triadic ties” that include other protesters (triangles in which two of a person’s ties share a tie between each other). These findings show protesters are a relatively cohesive community on social media. More than 80 percent of non-protesters, on the other hand, have no ties to others in their group, while just 40 percent of protesters have no such ties (see Figure 3).

This study captures the intuition that people are influenced by those they’re connected to when deciding when and how to protest, and the social networks of protesters are structured in dramatically different ways from those of non-protesters. It also shows that social media, and Twitter in particular, offer a window into real-time, networked protest activity that researchers can use to paint an even richer picture of the role of social ties in protest.

So, how do we apply these findings to our current moment of ongoing protests against police violence and anti-Black racism? First, it’s important to distinguish Charlie Hebdo protesters from Black Lives Matter protesters — the two groups protested in different political contexts with different goals, said Nagler.

He added that researchers can use this opportunity to take on what we left out of this study: “How do you draw in new people?” he asked, pointing out the novelty of Sen. Mitt Romney, Republican of Utah, joining Black Lives Matter protesters in Washington, D.C. “How do you draw in those who are not in the network? And if Romney’s there, does that mean he’ll draw in people from other networks who might not have otherwise joined?”

Read the Original Medium Post Here.