Who’s Attracted to a Clickbait Headline?

Older adults, Republicans, and independents, according to our research.

Credit: Judy Zhang

Area of Study

Tags

This article is part of CSMaP’s ongoing Research Summary series. We’ll provide quick, digestible versions of our published research articles for peer researchers, journalists, policymakers, and all those interested in the relationship between social media and politics. This week, we wrote about an experiment that tested the effects of clickbait headlines on news consumers.

A boy makes anti-Muslim comments in front of an American soldier. The soldier’s reply: priceless.

That was an Upworthy headline in 2013, when the viral news publisher was flying high as one of the “fastest-growing media sites” of all time. Its success was built on clickbait — a new type of headline at the time that tempted readers to click through to a story or video, usually by withholding information to build curiosity.

It worked: At its peak, Upworthy reached up to 85 million people each month. Until Facebook noticed users spent less time with clickbait and adjusted its algorithm to downgrade such content, which sent Upworthy’s business model over a cliff.

This kind of “information-gap” headline — pioneered by Upworthy, BuzzFeed, and others — fell out of fashion as social media platforms penalized publishers for what they felt was a poor user experience. But the economics of news consumption hasn’t changed since Upworthy’s decline: News consumers who once channel surfed in front of their TVs, or flipped the pages of a newspaper, can now choose from an unlimited amount of content on their social news feeds. This new social ecosystem forces media companies to compete for clicks on individual stories.

In other words, clickbait is here to stay. And it’s evolved into a more politically relevant form as Americans prepare to vote in 2020: partisan emotional clickbait, a term coined by researchers at the NYU Center for Social Media and Politics to describe headlines that appeal directly to the emotions of the partisan reader. With this in mind, our researchers ran two experiments to answer the following questions: Who is most likely to prefer these types of headlines? And what are the effects of consuming them?

“We were really interested in centering the act of clicking,” said Kevin Munger, an assistant professor of political science at Penn State, who teamed up with Sciences Po Ph.D. student Mario Luca, and our co-directors Jonathan Nagler and Joshua Tucker to complete the experiments. “We wanted to understand the individual choices news consumers make around these headlines and how they could drive politically relevant outcomes,” he added.

Here’s what we found: Older adults and non-Democrats — often Republicans or independents — showed a higher taste for clickbait. However, we also found that partisan emotional clickbait doesn’t seem to drive some of the most worrying trends among American news consumers, including affective polarization, or a growing dislike and distrust for those in the opposing political party.

Older adults and non-Democrats — often Republicans or independents — showed a higher taste for clickbait.

Here’s how we arrived at these findings: The researchers conducted two survey experiments and compared their results. They recruited about 2,800 participants for the first experiment using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, an online crowdsourcing marketplace that can produce nationally representative samples. The second experiment was a novel approach to survey recruitment: They ran a Facebook advertising campaign designed to attract people prone to clicking on eye-catching ads, which recruited a non-representative sample of about 1,230 participants who finished the survey.

During each survey, participants were asked questions about their demographic information, partisan group identity, and how they engage with different types of media, including social media platforms. They were shown headlines and asked which ones appealed to them most, allowing the researchers to calculate each participant’s preference for clickbait.

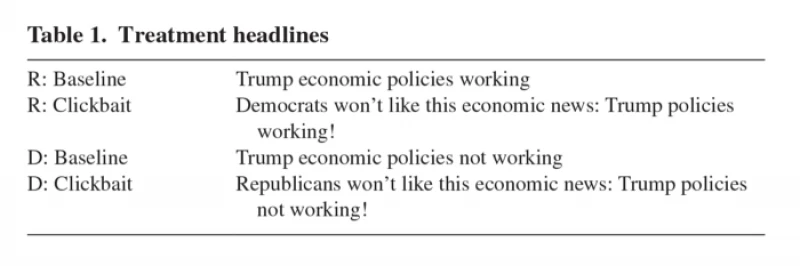

The participants were then asked to read a news story by CNN Money — considered a politically neutral source — that reported findings from a recent jobs report released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Participants were randomly assigned one of four “treatment headlines” to find out how they felt about partisan groups after reading it (see Table 1), which tested for affective polarization. They were asked about their confidence in both online and traditional news, which measured the effects of clickbait on trust in media. Finally, they were asked multiple-choice questions about facts presented in the story, which tested for information retention.

The results were surprising: The experiments failed to show evidence that partisan emotional clickbait has direct effects on affective polarization, trust in media, and information retention. The only consistent results predicting a taste for clickbait was age (older adults prefer such headlines) and affiliation with the Democratic Party (left-leaning participants tend to avoid such headlines).

We’re confident in these results because we observed them across separate populations — the two samples we recruited via MTurk and our Facebook ad campaign. But we should still note that some variables were associated with a preference for clickbait in one sample, but not the other. Users with more education in the Facebook sample don’t like clickbait, for example, while frequent Facebook users in that same sample show a taste for it.

These findings can be explained by what communications scholars call the Era of Minimal Effects, Munger said, in which fractured and elective news consumption yields little to no effect on consumers. “Anyone who consumes a decent amount of media has already seen these kinds of headlines and are unlikely to find them very compelling in the context of a media effects survey experiment like this,” he added.

Munger is working on another experiment that could explain the taste for clickbait among non-Democrats, though he cautions the findings are preliminary: Republicans could be embracing clickbait as a form of resistance to the influence of mainstream media, which builds credibility based on reporting standards.

“They are explicitly rebelling against mainstream media in their choice to embrace clickbait,” he said.

Read the Original Medium Post Here.