- Home /

- Research /

- Reports & Analysis /

- Egyptian Elections on Twitter, Far More Interesting Than Egyptian Elections

Egyptian Elections on Twitter, Far More Interesting Than Egyptian Elections

The meager voter turnout at Egypt's first parliamentary elections since 2012 has been chalked up to apathy and frustration among Egyptian citizens, but an analysis of 500,000 tweets indicates that citizens’ distrust, exclusion and alienation from Egyptian politics is to blame.

Credit: Flickr

Authors

Area of Study

This article was originally published at The Washington Post.

Polls have closed, and Egyptian President Abdel Fatah al-Sissi has emerged, unsurprisingly, as the true victor in Egypt’s first parliamentary elections since the ouster of Mohamed Morsi in 2012. Winning landslides in both rounds of voting, For the Love of Egypt—a pro-Sissi electoral alliance—will enter parliament with the 120 seats allocated to winner-takes-all party lists. The coalition is expected to rubber stamp almost 200 laws that the president has passed by decree since coming to power in June of 2014.

From the start, Egyptian news outlets and even party leaders lamented the “boring” nature of the parliamentary elections. Meager voter turnout—despite election holidays and fines for failing to appear at the polls—has been chalked up to apathy and frustration among Egyptian citizens.

But Twitter tells a different story.

Analysis of over 500,000 tweets referring to Egypt’s parliamentary elections indicates that low levels of voter participation should not be dismissed as mere indifference or fatigue. Instead, data collected by New York University’s Social Media and Political Participation (SMaPP) Lab between June 1 and Dec. 3 suggests that citizens’ distrust, exclusion and alienation from Egyptian politics is to blame.

Where and when people tweeted about the elections

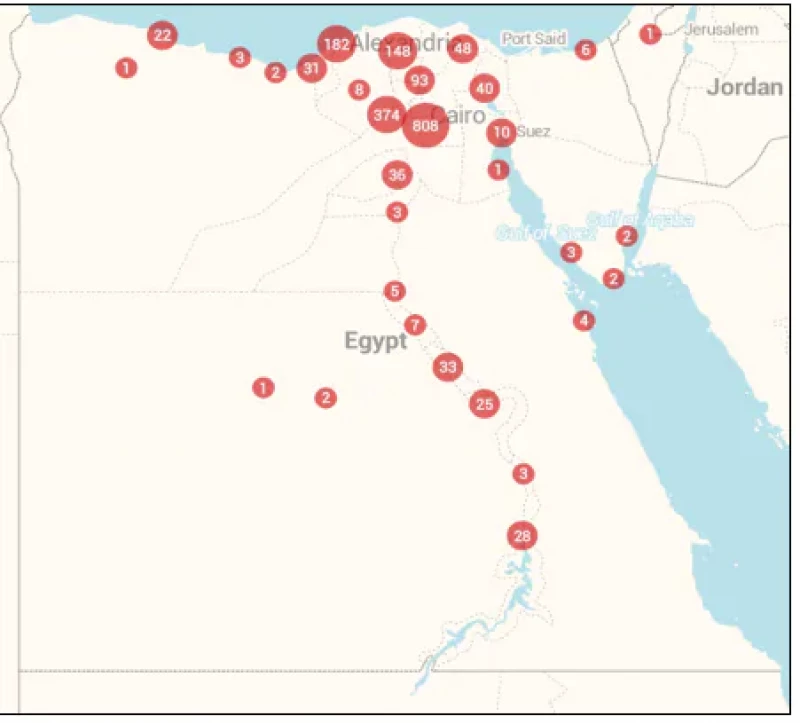

As the map of geolocated users below suggests, Egyptians discussing the elections on Twitter were geographically diverse, not simply concentrated in Cairo. Outside of Egypt, users from Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the United States also tweeted about the elections in large numbers. This reflects not only the high levels of Twitter penetration in these countries but also the frequency with which Egyptian expatriates from the United States and the Gulf states voted—especially in the second phase of the election.

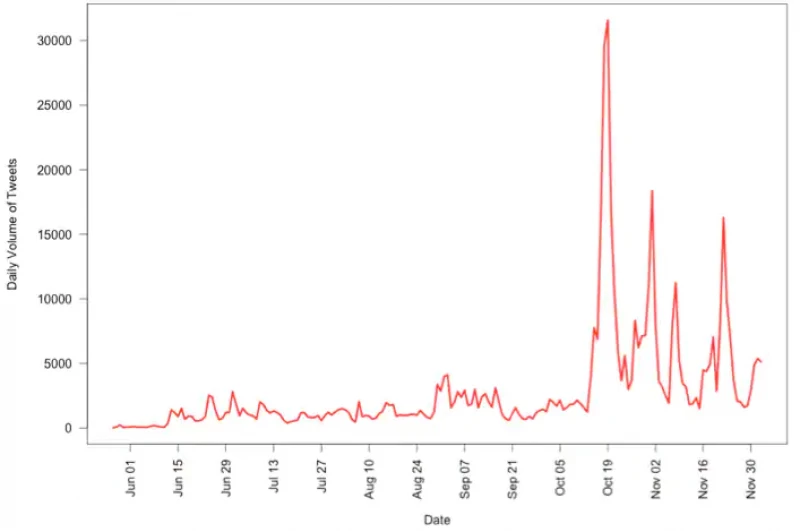

Although voter turnout increased slightly both in Egypt and abroad during the second round of voting, the volume of tweets referencing the elections peaked most dramatically during the first vote in mid-October. This pattern was likely driven by regional and international news coverage of the elections, which paid less attention to the voting process after the initial round.

It’s not just apathy keeping voters from the polls

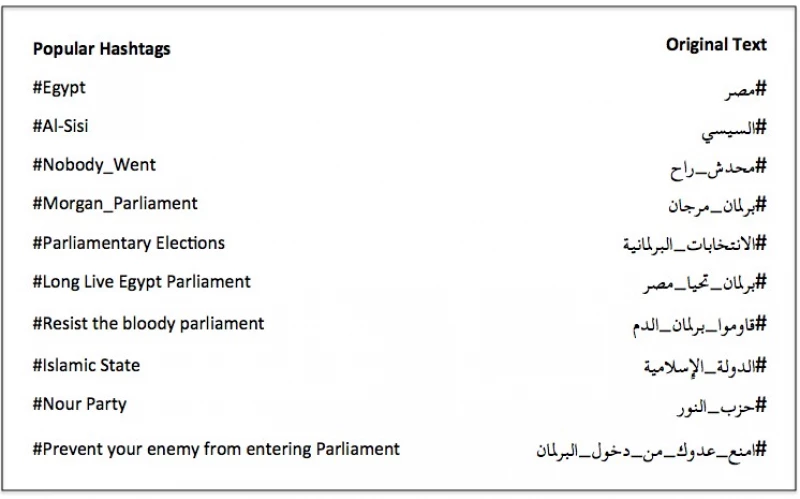

Many Egyptian Twitter users turned to humor and pop-culture references to justify their decisions to stay home from the polls. The Egyptian dialect hashtag “NobodyWent,” was particularly popular. It emerged following the spread of the #insteadof_voting hashtag, which made sarcastic suggestions of activities that would be more enjoyable than voting from shopping to mourning the depreciation of the Egyptian pound. As in the mainstream news media, low turnout was a common topic in the discussion of the elections on Twitter, appearing in these popular hashtags or referenced explicitly in over 14,000 tweets in the dataset.

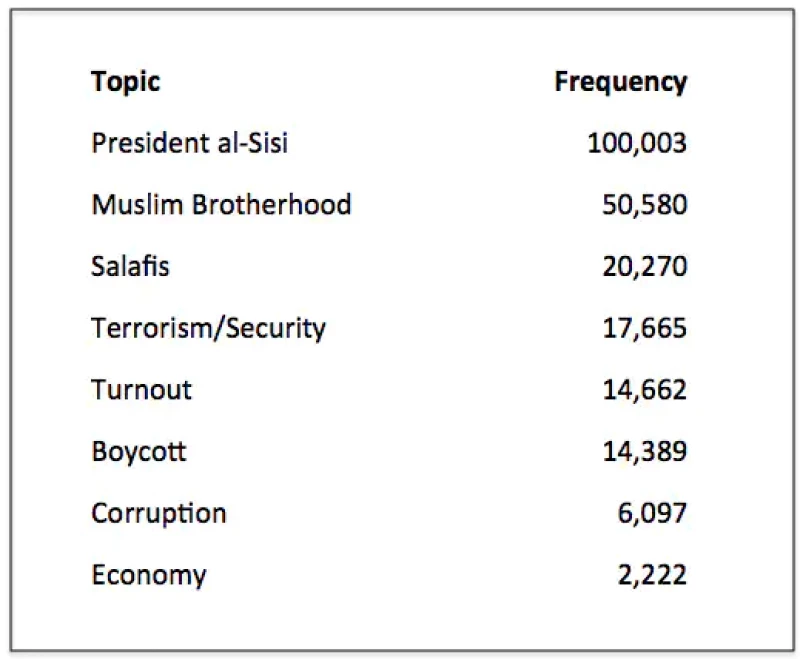

Another popular hashtag, #Morgan_Parliament, alludes to a 2007 Egyptian film starring Adel Imam, “Morgan Ahmad Morgan.” The film follows an unscrupulous businessman who runs for parliament in order to obtain immunity and protect his wealth. As this pithy hashtag suggests, many Egyptian Twitter users distrust the electoral process due to reports of vote buying and fraud, the banning of the Muslim Brotherhood, boycotts by other parties and a general lack of political openness. Along these lines, discussions of the Muslim Brotherhood and boycotts were quite common in the data, as these topics were mentioned 50,580 and 14,662 times respectively.

For many Egyptians, the parliamentary elections appeared to be a lose-lose choice between ultra-conservative Salafi Islamists and continued military rule. While some dealt with this Catch-22 by joking about staying home from the polls, other Twitter users saw the elections more explicitly as a symbol of continued political oppression. For example, versions of the Arabic hashtag “Resist the bloody parliament” were quite popular in the data, suggesting an extreme aversion to the electoral process as a whole.

Voting is not necessarily “democratic”

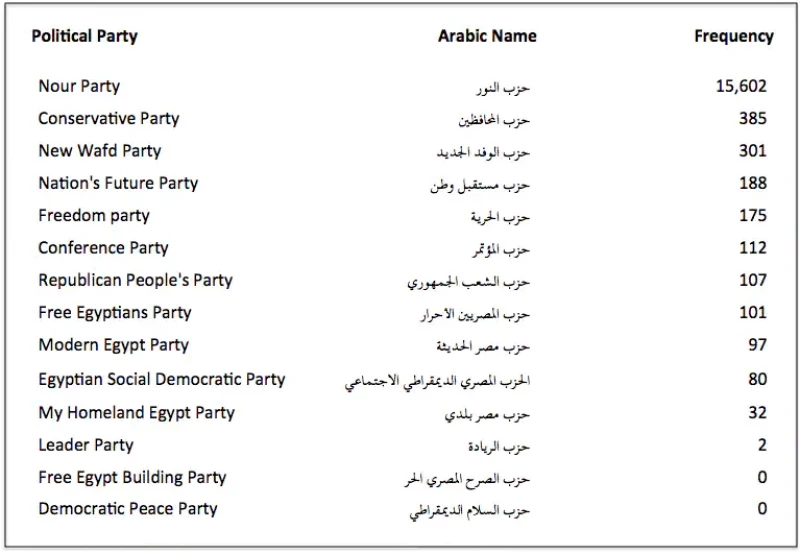

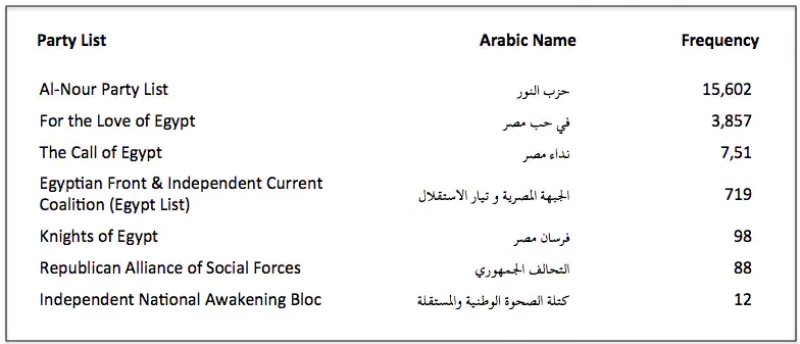

The hashtags and topics commonly tweeted by those who actually advocated participation in the elections were no more encouraging. While references to Sissi and hashtags touting his slogan “Long Live Egypt” were quite common—appearing more than 100,000 times in the dataset—there was relatively little discussion of the political parties and coalitions actually competing in the election.

With the exception of the Salafi al-Nour party—arguably the biggest loser of the elections—political parties and blocs received very little attention on Twitter. Additionally, a significant portion of the tweets that reference Salafis were not sent by their supporters but rather by pro-Sissi Twitter users trying to drum up fears of a Salafi electoral victory.

The emergence of the Arabic hashtag “Prevent your enemy from entering Parliament” was just one example of this fear mongering. Adopted as a get out the vote slogan, especially among pro-Sissi Twitter users, the message portrays voting as a battle through which “enemies” must be defeated.

Although these popular hashtags and topics paint a discouraging picture of more “engaged” Egyptian voters, such rhetoric should come as no surprise given the rise of vitriolic polarization in the post-Egyptian coup period.

Consequences of polarization and political exclusion

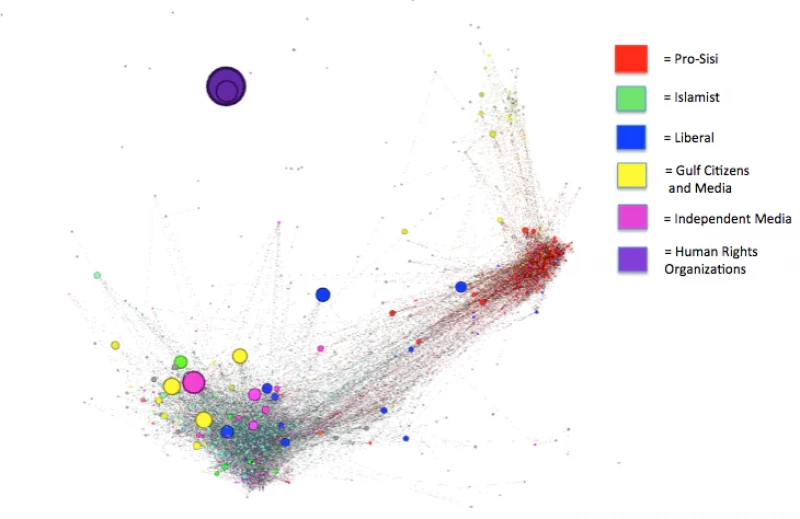

The retweet network structure below highlights the polarized manner in which Twitter users discussed the parliamentary vote online. The Sissi supporters—represented by red dots—appear clustered together, primarily engaging with like-minded users. Recent research suggests that this kind of ideological echo chamber may reinforce existing political divisions and deepen polarization both on and offline.

Users in the network who are more closely connected to one another pull closer to each other in the layout, while less connected users drift further apart due to the attraction of more strongly connected users. Node or dot size is determined by indegree centrality—how often a user is retweeted.

This brief look at the discussion of the Egyptian elections on Twitter suggests that, while perhaps unsurprising, the current political climate is anything but boring. In a vehemently polarized atmosphere, incentives to vote are often driven by fear and revenge. Against this backdrop, alienation from formal electoral channels should be viewed not as mere political apathy, but rather as a symptom of living in a repressive political environment.

The consequences of these exclusionist policies are especially visible in Egypt today, as politically marginalized Islamists increasingly turn to violence to achieve their goals. As long as Egyptian politics remains a zero-sum game from which entire ideological groups are excluded or sidelined, extremists will continue to garner support and reasonable appeals for compromise will fall on deaf ears.

Alexandra Siegel is a graduate student researcher in the New York University Social Media and Political Participation (SMaPP) Lab and a Ph.D. candidate in Wilf Family Department of Politics at NYU. You can follow her @aasiegel