- Home /

- Research /

- Reports & Analysis /

- Twitter Banned Marjorie Taylor Greene. That May Not Hurt Her Much.

Twitter Banned Marjorie Taylor Greene. That May Not Hurt Her Much.

She’s gaining followers and ‘likes’ on other social media platforms, our research finds.

Credit: Gage Skidmore

Authors

Tags

This article was originally published at The Washington Post.

Earlier this month, after Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) tweeted misinformation about coronavirus vaccines for the fifth time, Twitter permanently suspended her personal account. (It left her official congressional account intact.) The next day, Facebook suspended her account for 24 hours for the same post.

These bans are part of social media platforms’ shift in policy, which began in late 2020 as the companies began applying the same rules to elected officials that they do to other users. Many noticed the change a year ago, after the Capitol insurrection, when Twitter, Facebook and YouTube permanently suspended President Donald Trump’s accounts for the potential to incite violence.

But does deplatforming politicians matter?

In some cases, right-wing Internet celebrities who were permanently deplatformed have gone bankrupt or resorted to selling vitamins on eBay or grifting. But for politicians, especially right-wing politicians like Greene, bans may be less effective because they can turn to other outlets to reach their most ardent supporters. Such outlets include what supporters call “free-speech” platforms like Gab or Gettr, national party support such as fundraising, and even national news media.

We find that Greene continues to receive high levels of engagement across platforms relative to the engagement she received on her now-banned account — and in the week since the ban, her following increased on all platforms for which she maintains accounts. She has also continued to post about her skepticism of mask mandates and vaccines across other platforms.

Greene can still engage on other social media platforms

Being thrown off Twitter but no other social media means Greene still has many ways to communicate with voters or supporters who might want to talk about her to their friends and family or donate to her campaign. Of course, she can still communicate on mainstream platforms like Facebook and Instagram. But in addition, she can use accounts on libertarian platforms like Parler, Gab and Gettr. These tout the fact that they don’t moderate content, which brings in millions of Republicans disdainful of what Greene called “Big Tech censorship.” She also maintains her account on Telegram, a messaging platform known in developed countries for taking in far-right users who’ve been banned by mainstream platforms.

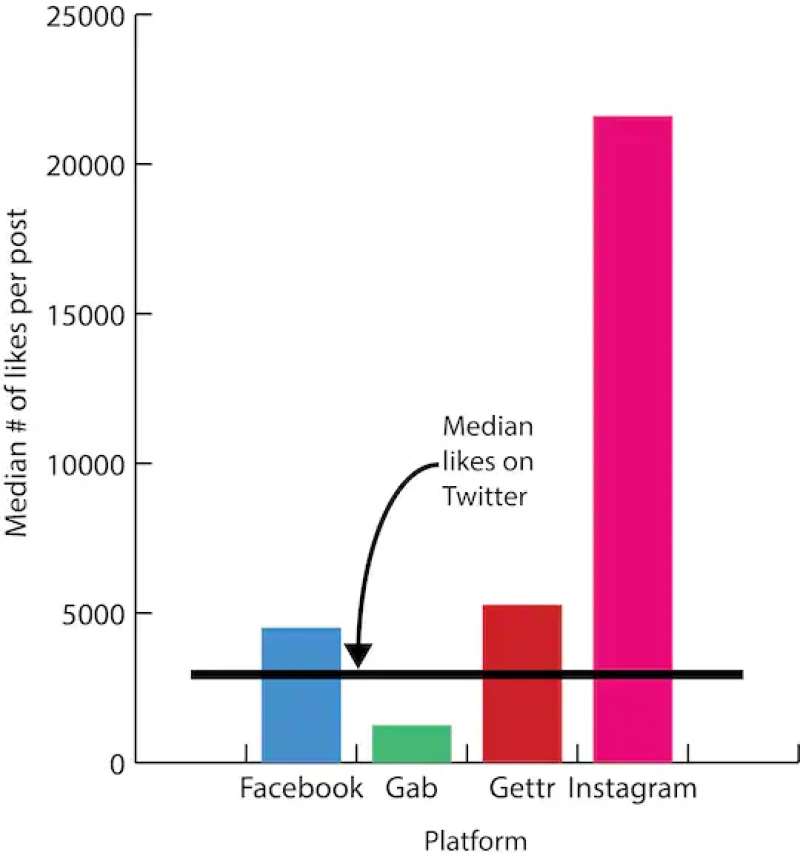

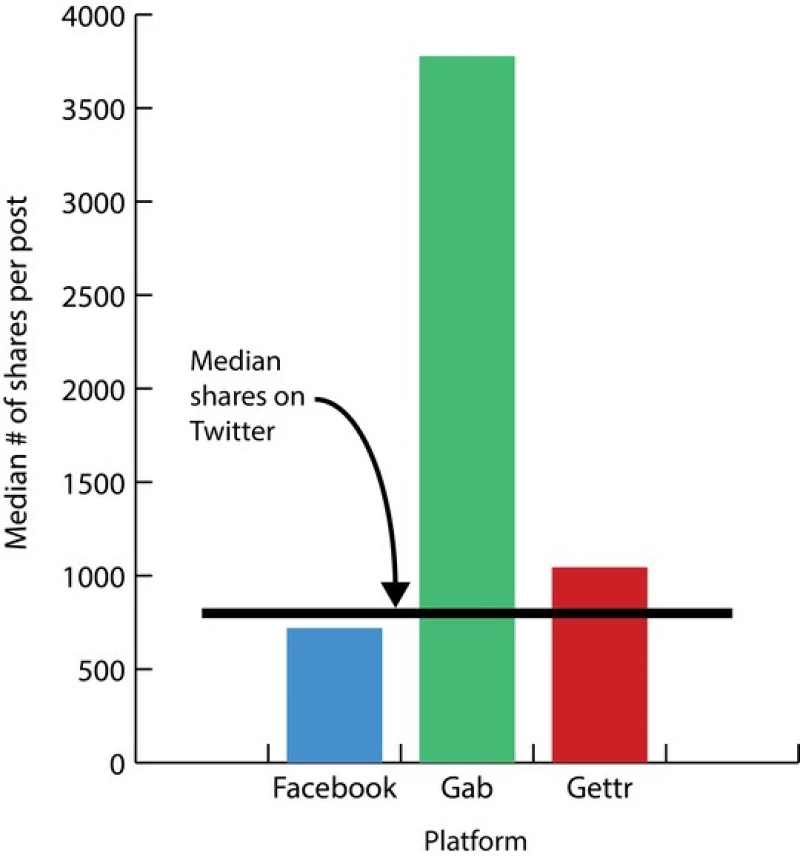

To find whether Greene has reached as many people on those platforms as she did on Twitter, we collected her posts, including the number of likes and shares, on those platforms in the days since her Twitter account was banned. In brief, she did, as you can see in the figures below. We charted the median number of likes per post and the median number of shares per post that Greene has received on each platform since she was thrown off Twitter. The solid horizontal line shows the median engagement (by which we mean likes and shares, respectively) she got on her personal Twitter account before she was banned.

On all platforms except for Gab, Greene received more likes than she did on her personal Twitter account. And on all platforms, after the Twitter suspension, she received close to or more shares than she received on Twitter before the ban. We don’t include Instagram in “shares” because public shares are not a function of the platform.

In other words, despite her Twitter ban, Greene remains popular both on other mainstream social media platforms and on alternative platforms.

Greene’s following increased on other platforms after her Twitter ban

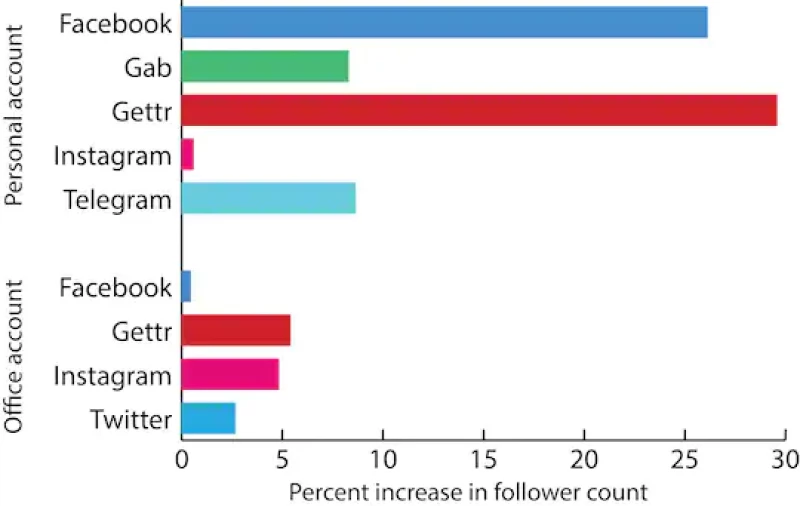

What’s more, in the week after Twitter banned her, Greene attracted more followers on other platforms than she had had before, as you can see in the figure below. This increase is particularly striking on her Facebook and Gettr accounts, where followers increased more than 25 percent. This aligns with what we’ve found in previous research: Content halted on one platform can spread to other platforms that don’t have the same moderation standards, and content moderation on one platform can send people to other platforms.

What could this mean for Greene going forward?

Of course, politicians prefer to have access to all available audiences and potential supporters. But losing one or even two social media platforms does not necessarily devastate their political goals. Greene can still reach her followers on other platforms. What’s more, the Twitter ban lets her talk about how she is being silenced, ask for donations to fight what she calls censorship, and compare herself to Trump, who was deplatformed last year.

In other words, the Twitter ban hasn’t hurt Greene’s ability to spread her message. Instead, it seems to have given her a message of grievance, which she is leveraging to increase her brand and online presence. While Twitter may have stopped Greene from spreading vaccine misinformation on its own platform, it has not hurt her ability to spread that same misinformation elsewhere.

It’s possible that by throwing Greene off the platform, Twitter has shown other politicians that there are costs to spreading vaccine misinformation. But if so, so far, Greene isn’t paying them.

Of course, the presence of alternative platforms doesn’t mean that individual platforms have no recourse when politicians break the rules. If they want to limit the spread of vaccine misinformation on their platforms, tools like warnings, suspensions and bans still matter. But our findings reinforce the idea that content moderation works best at an ecosystem level — or misinformation will simply change venues and keep spreading elsewhere.

Maggie Macdonald (@MG_Macdonald) is a postdoctoral fellow at NYU’s Center for Social Media and Politics.

Megan A. Brown (@m_dot_brown) is a research scientist at NYU’s Center for Social Media and Politics.