- Home /

- Research /

- Reports & Analysis /

- Gender-Based Online Violence Spikes After Prominent Media Attacks

Gender-Based Online Violence Spikes After Prominent Media Attacks

Our research finds that after a prominent male media personality targets a female journalist, the prevalence of hateful speech targeting those journalists increases in the immediate aftermath, often taking days to decrease.

Credit: Gage Skidmore

Authors

- Megan A. Brown,

- Zeve Sanderson,

- Maria Alejandra Silva Ortega

Area of Study

Tags

This article was originally published at Brookings.

On March 9, 2021, Fox News host Tucker Carlson took aim at a favorite target: a New York Times journalist. In the crosshairs was tech reporter Taylor Lorenz, one of the paper’s rising stars who had recently described the toll of online harassment. The torrent of online hate she receives had “destroyed her life” she said, in a tweet supporting the launch of the Online Violence Response Hub.

“Destroyed her life, really? By most people’s standards, Taylor Lorenz would seem to have a pretty good life, one of the best lives in the country, in fact,” Carlson intoned. “Lots of people are suffering right now, but no one is suffering quite as much as Taylor Lorenz is suffering.”

After Carlson mocked Lorenz in his segment, her social media mentions and inbox were again filled with violent threats and harassment—a dynamic likely familiar to many women with a public presence online. The vitriol Lorenz endured was an example of gender-based online violence, which UNESCO recently characterized as online rhetoric against women designed to “induce fear, silence, and retreat; and … chill their active participation” in public debate. Yet as problematic as the phenomenon is, it remains relatively understudied. To better understand how gender-based online violence takes place, we therefore examined three instances in which female journalists were attacked by prominent male media figures on either social media or broadcast media, and then tracked the ways in which online violence against them spiked.

In order to analyze the relationship between attacks by prominent media figures and the quality of online discussion, we—NYU’s Center for Social Media and Politics and the International Women’s Media Foundation—collected data on three case studies: Carlson’s targeting of Taylor Lorenz above, the journalist Glenn Greenwald’s targeting of Lorenz on Twitter, and Carlson’s targeting of Virginia Heffernan in a separate segment on Fox News.

Our analysis used large-scale quantitative data to assess how the public conversation surrounding these journalists changed in the aftermath of being targeted by prominent media personalities. The research findings showed sharp increases in harmful speech after the journalists were targeted by Carlson and Greenwald.

For each of the three case studies, we first collected tweets that mentioned Lorenz or Heffernan (either by their name or Twitter handle) in the days before and after they were targeted by Greenwald or Carlson. Next, we examined the content of these tweets for a variety of factors: their toxicity (content likely to deter someone from participating in a conversation); the presence of threats, insults, or identity attacks; and whether the comments were sexually explicit. We did so using Perspective, an open source tool created by Jigsaw and Google that allows us to measure harmful content in text.

These values were scored from 0 to 1, where items scored closer to one are more likely to contain harmful text. We then plotted the 24-hour moving average of toxicity, threat, insult, identity attack, and sexually explicit tweets before and after a figure targeted a female journalist. By taking the average of these scores for a given time period, we can approximate the proportion of these tweets that were harmful.

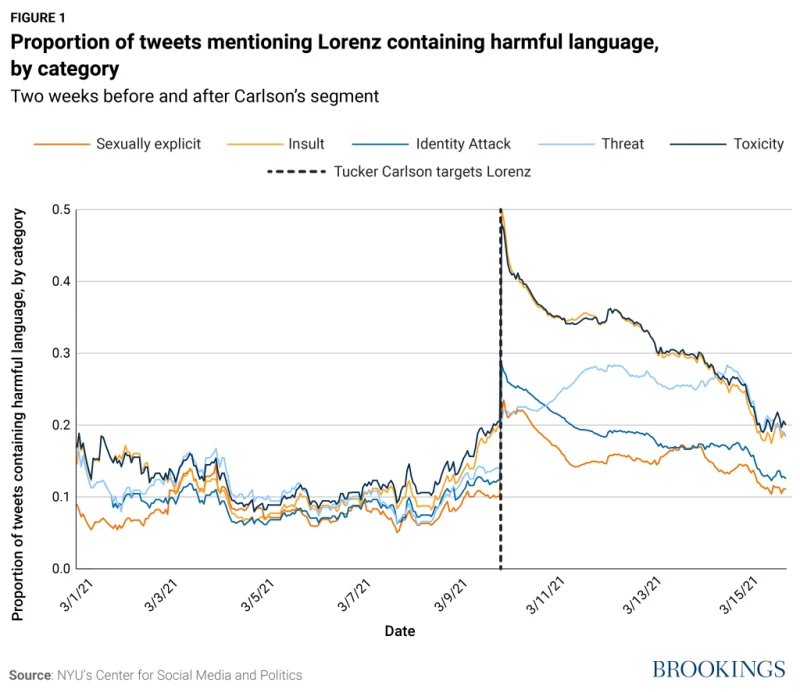

After Carlson targeted Lorenz in a segment on his Fox News show, we found that one in two tweets mentioning Lorenz contained either toxic or insulting language. Overall, the rate of harmful speech in her mentions increased by 115% following Carlson’s segment. Figure 1 plots the change in the online conversation around Lorenz following Carlson’s attack.

Figure 1

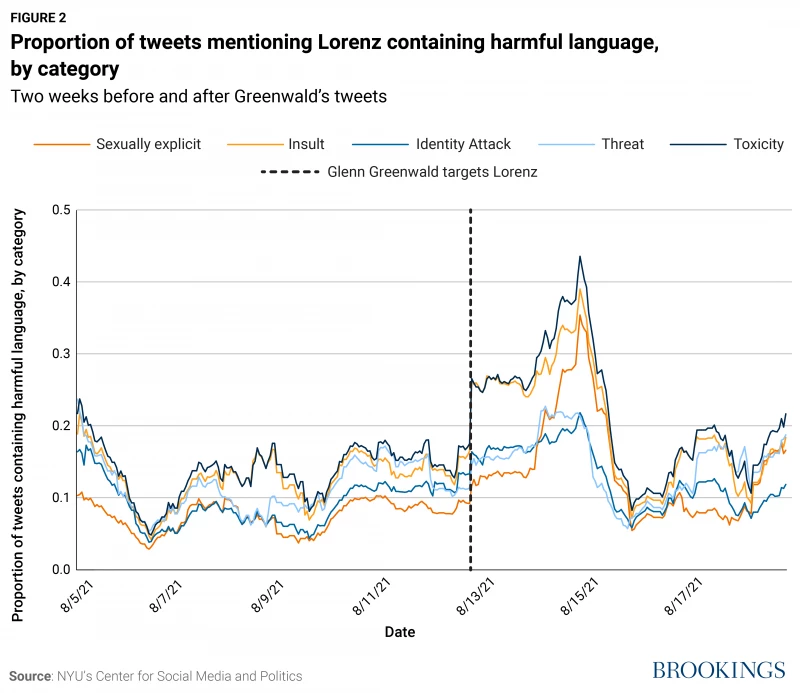

In Figure 2, we plot the 24-hour moving average of tweets before and after Greenwald targeted Lorenz. The figure shows that after Greenwald’s attack, the likelihood that tweets mentioning Lorenz would contain harmful speech increased by 144%, peaking on Aug. 15, 2021, two days after he targeted Lorenz.

Figure 2

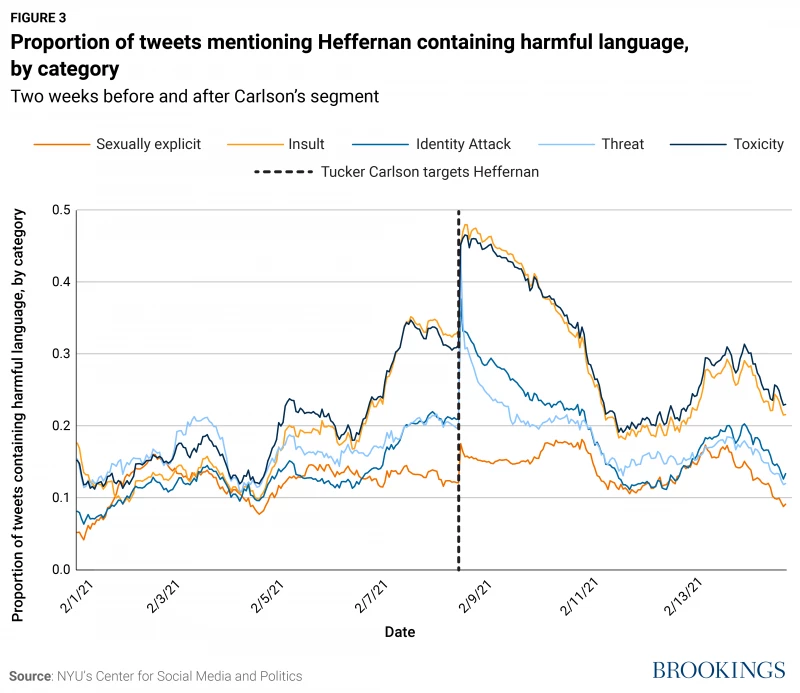

Finally, we constructed a similar time series examining the online conversation around Heffernan after she was targeted by Carlson in a segment on March 9, 2021. Subsequently, the likelihood that tweets mentioning Heffernan would contain harmful language increased by 65%.

Figure 3

Taken together, these figures describe a disheartening trend: After a prominent male media personality targets a female journalist, the prevalence of hateful speech targeting those journalists increases in the immediate aftermath, often taking days to decrease. As Carlson’s initial quote above illustrates, prominent male journalists themselves often downplay the severity of online violence against women. Yet the attacks can have serious implications, including becoming full blown gendered disinformation campaigns that seek to silence the voices of female journalists by undermining their credibility.

Unfortunately, the online violence Lorenz and Heffernan have experienced is neither uncommon nor limited to the United States. In the Philippines, for example, President Rodrigo Duterte has made the journalist and Nobel Peace Prize winner Maria Ressa a frequent target of attack in speeches and statements, exposing her to vitriolic disinformation and harassment campaigns. Her experience exemplifies an alarming trend. In a report released by the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) and UNESCO last year, researchers found that 73% of the women journalists surveyed had experienced online violence, and one third of these women reported experiencing a physical attack that they believed was related to the online harm they experienced. Research indicates that nearly 30% of women journalists who have experienced these attacks have considered leaving the profession as a result. The private implications of this type of harassment are well documented, including in police reports for stalking and threatening emails and direct messages.

Speaking to us, Lorenz emphasized the gendered nature of her harassment. “It is not a coincidence that when Tucker Carlson pulled up my account on air that they replaced my Twitter profile picture with a picture from 8 years ago to try to paint me as a Gen Z Tik Tok reporter.” Lorenz receives death threats daily, and on several instances has had strangers show up in her neighborhood looking for her. Online trolls have spread disinformation about her, ranging from falsehoods about where she went to college to accusations about her stalking teenagers on the internet. “We have all dealt with jerks online; it is this reputational harm that creates long term damage,” Lorenz says. “It is smears, changing the narrative about you, reframing your stories in a controversial way, that is the really harmful stuff.”

Fortunately, there are some resources to help women journalists when they face attacks online. For example, the Coalition Against Online Violence, a group of nearly 50 press freedom, technology, human rights, and news organizations organized by the International Women’s Media Foundation, is providing women journalists with a support system to protect them. The IWMF and ICFJ also provide access to those resources through the Online Violence Response Hub.

Yet preventing gender-based online violence remains a challenge. Although many online platforms have taken steps to address these attacks, there is still a lot of work to be done to ensure the safety of female journalists online. Even more, analysis of the phenomenon is at an early stage. Further research is needed to better understand both the short- and long-term impacts of online violence on female journalists and their role in public discourse.

Megan A. Brown is a research scientist and data engineer for the Center for Social Media and Politics at New York University (CSMaP).

Zeve Sanderson is the Founding Executive Director of CSMaP.

Maria Alejandra Silva Ortega is a senior program coordinator at the International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF).