How Many People Live in Echo Chambers on Social Media?

Our research shows political bubbles, or echo chambers, are not as widespread as many pundits make them out to be.

Credit: Judy Zhang

Area of Study

Tags

This article is part of CSMaP’s ongoing Research Summary series. We’ll provide quick, digestible versions of our published research articles for peer researchers, journalists, policymakers, and all those interested in the relationship between social media and politics. This week, we wrote about our research on political bubbles, which shows they’re not as widespread as many pundits make them out to be.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made people more reliant on social media than ever: Users are turning to platforms such as Facebook and Twitter to reach loved ones and access real-time news updates. Facebook alone reported record usage across its apps as governments around the world began ordering their citizens to stay indoors to stem the spread of the virus.

A surge in social media use could have widespread implications for one of the most defining features of American politics: political polarization, or the vast and growing gap between liberals and conservatives. Many observers — including former President Barack Obama — believe social media use encourages the formation of online “political bubbles,” or echo chambers in which users consume and share information aligned with their own ideological beliefs. Some even point to these bubbles as the reason “why [Donald] Trump won and you didn’t see it coming.”

But is there empirical proof behind this argument? In 2016, researchers at the Social Media and Political Participation Lab, now housed at the Center for Social Media and Politics at NYU (CSMaP), ran a study to find out. They found little evidence to support the narrative about “digital islands of isolation” that drift further apart each day, as one journalist put it. Rather, they found most Twitter users consume news diets that overlap more than they diverge.

As we approach the 2020 U.S. presidential election, we thought it would be a good time to revisit the study and explore its findings in a global pandemic context. What follows is a summary of the study’s findings and contributions to what we know about people’s exposure to diverse information online.

The researchers — who include Gregory Eady, Jonathan Nagler, Andy Guess, Jan Zilinsky, and Joshua A. Tucker — surveyed nearly 1,500 nationally representative Americans. They linked the survey to data from each respondent’s public Twitter account, including the accounts they followed (more than 640,000) and tweets posted by those accounts (about 1.2 billion). They separated respondents into five groups, or quintiles, based on where they fell along the political spectrum, which they self-reported in the survey.

Their goal was to paint a nuanced picture of the information people are exposed to on Twitter, and in particular, to find out how many of those people live in ideological bubbles. They took three steps to achieve this:

Examine the ideological distributions of the accounts respondents followed, which were divided into three groups: members of the media, members of the political class, and non-elite members of the general public.

Examine the ideological distributions of tweets users see in their feeds — both overall and from each of the three groups above.

Determine whether tweets respondents saw from accounts they don’t follow were more ideologically diverse or moderate than tweets posted by those they do follow.

Here’s what they found:

More than a third of respondents didn’t follow a single media account while more than half didn’t follow a political account, but many followed more than one of each: 18 percent followed 11 or more media accounts and 7 percent followed 11 or more political elites.

Stronger partisans were more likely to follow media and political accounts than moderates. In other words, their following behavior was more politically engaged than that of other respondents.

There would be clear evidence of people residing in online ideological bubbles if all liberals only followed liberal media sources and all conservatives only followed conservative media sources. The results, however, were much more nuanced:

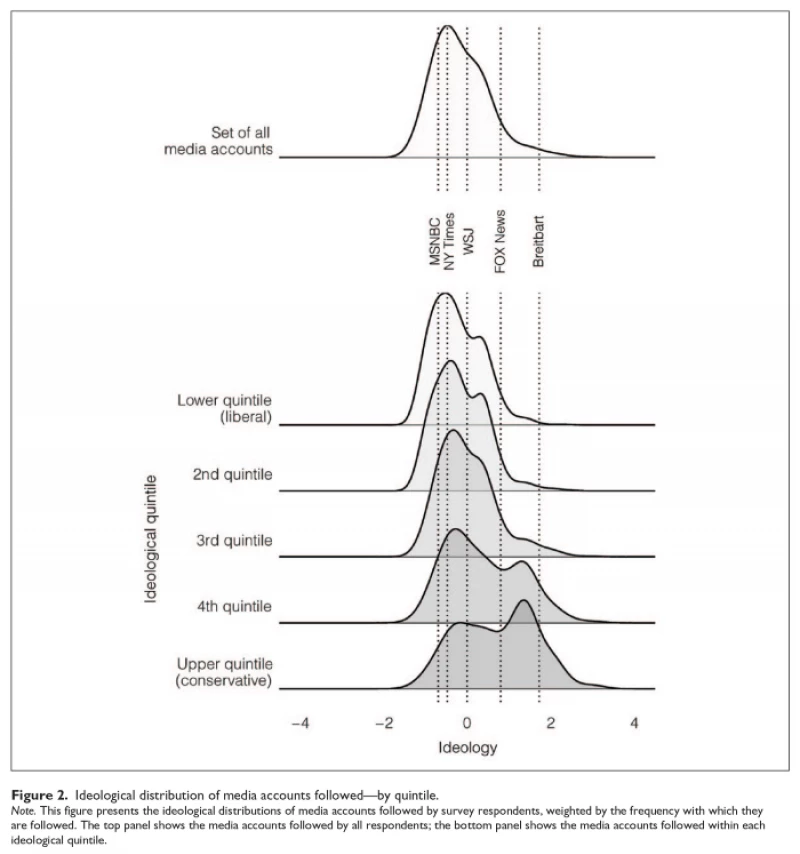

They saw a substantial overlap in the ideological distributions of media accounts followed across quintiles, as shown in Figure 2 from the article. Each group follows media accounts both to the left and right of the New York Times, though the region to the left of the New York Times is much smaller for the most conservative quintile.

The most conservative quintiles show distributions with two modes: one in the mainstream center and one to the right between Fox News and Breitbart.

About 71 percent of media accounts followed by the most liberal quintile fell to the right of MSNBC, though virtually all of these accounts were also to the left of Fox News.

In contrast, about half of media accounts followed by those in the most conservative quintile are at least as far to the right as Fox News, suggesting more concentrated following behavior among that group.

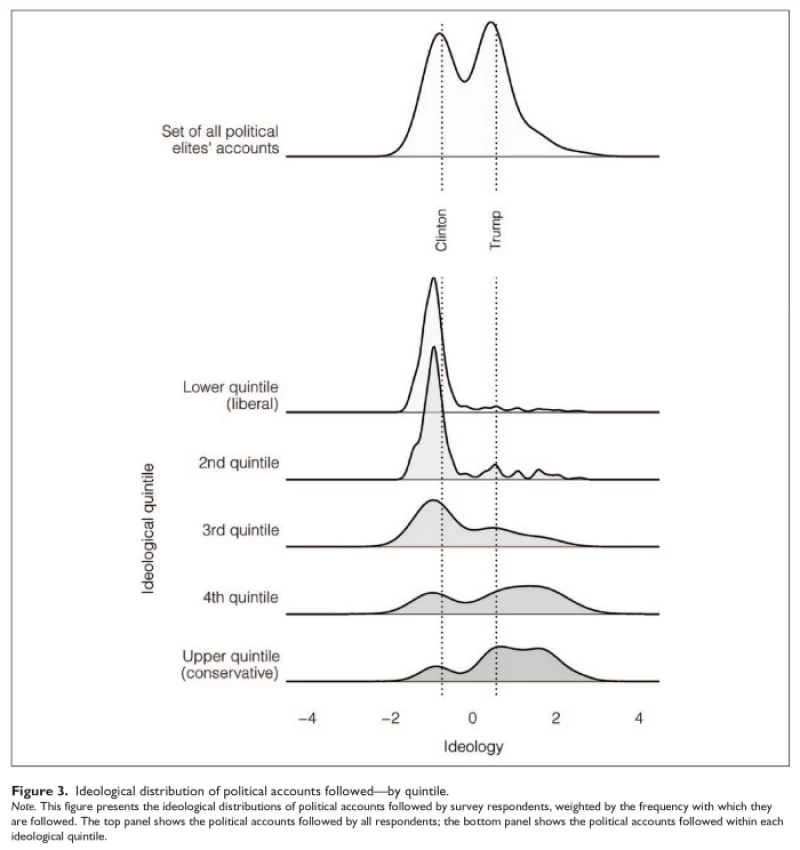

The researchers found much clearer separation when plotting the ideological distribution of politicians followed by each quintile:

Respondents in the most conservative and most liberal groups clearly chose to follow politicians who fall to the left or right of the zero point in Figure 3. In fact, they mostly follow politicians to the left of Hillary Clinton and to the right of Donald Trump.

The distributions show that following behavior around media accounts is less polarized than that of political and non-elite accounts. This suggests many people are following media sources that are more moderate on average than the friends or politicians they follow.

So, which users live in ideological news bubbles? The researchers define this group as liberals who don’t follow a minimum proportion (at least 5 percent) of conservative media accounts (those at least as far right as Fox News), and conservatives who don’t follow the same minimum proportion of liberal media accounts (those at least as far left as MSNBC). By this measure:

84 percent of those in the most liberal quintile, along with 85 percent in the second-most liberal quintile, live in a bubble.

A smaller proportion (78 percent) of those in the most conservative quintile live in a bubble. Among the most conservative respondents (the rightmost 5 percent), 42 percent followed media accounts at least as far left as MSNBC.

This asymmetry between liberals and conservatives could be explained by the nature of supply and demand for news: People across the political spectrum follow mainstream news organizations committed to journalistic norms, despite perceptions — especially among conservatives — of their left-leaning bias.

While conscious following activity reflects what respondents choose to see, the researchers also considered what they didn’t choose: tweets posted by accounts they don’t follow, which appear in their feeds due to likes and retweets by those they do. Such retweets could lead to a more balanced information diet than a user’s following behavior might indicate:

While 16 percent of respondents in the most liberal quintile chose to follow accounts as far to the right as Fox News, 27 percent in the same quintile get some share of their Twitter news diet from tweets at least as far right as Fox News

While 22 percent of conservatives chose to follow media accounts as far to the left as MSNBC, 43 percent get some part of their Twitter news diet from accounts at least as far to the left of the network

These findings don’t suggest users live in narrowly defined “bubbles,” in which Twitter users self-segregate and only consume news that aligns with their belief systems. The researchers found more overlap than divergence in the ideological distributions of media accounts followed by the most liberal and most conservative respondents in their sample. In other words, if we picked a liberal and conservative at random, just over half the media accounts they follow would come from the same segment of the ideological distribution.

Still, they found an overwhelming majority of liberals weren’t exposed to media as conservative as Fox News. Conservatives in turn weren’t exposed to media as liberal as MSNBC. This could mean large parts of the American public don’t know what kind of information their fellow citizens are absorbing, which could lead to their inability to understand how those on the opposite side of the political spectrum form their views.

Here’s an important caveat: These findings may not always translate to offline media exposure, which the researchers show by asking users in the survey about their TV news-watching habits. Many respondents with unbalanced online media diets said they spent time watching TV news from diverse sources, which highlights the importance of considering offline behavior when studying online political bubbles. It’s why focusing exclusively on online behavior can overstate the existence of unbalanced media diets among social media users.

We can’t be certain how these findings will hold up in a global pandemic information environment, in which users spend more time online and seek out more news. But we don’t expect liberals to turn to Fox News for information about COVID-19, nor do we expect conservatives to turn to MSNBC to do the same.

And how could the current information environment affect polarization and how voters make up their minds ahead of the 2020 election?

“We could be in an online information environment where many liberals read New York Times and Washington Post stories about the Trump administration’s mismanagement of the crisis, but miss Fox News stories read or viewed by conservatives, which tend to downplay the administration’s response,” said Nagler, our co-director and a professor of politics. “Many of these liberals could indeed fail to understand how many conservatives — whose information is largely mediated by Fox News and other news sources to the right — approve of the administration’s response and plan to vote to re-elect Trump.”

Read the Original Medium Post Here.