- Home /

- Impact /

- Policy /

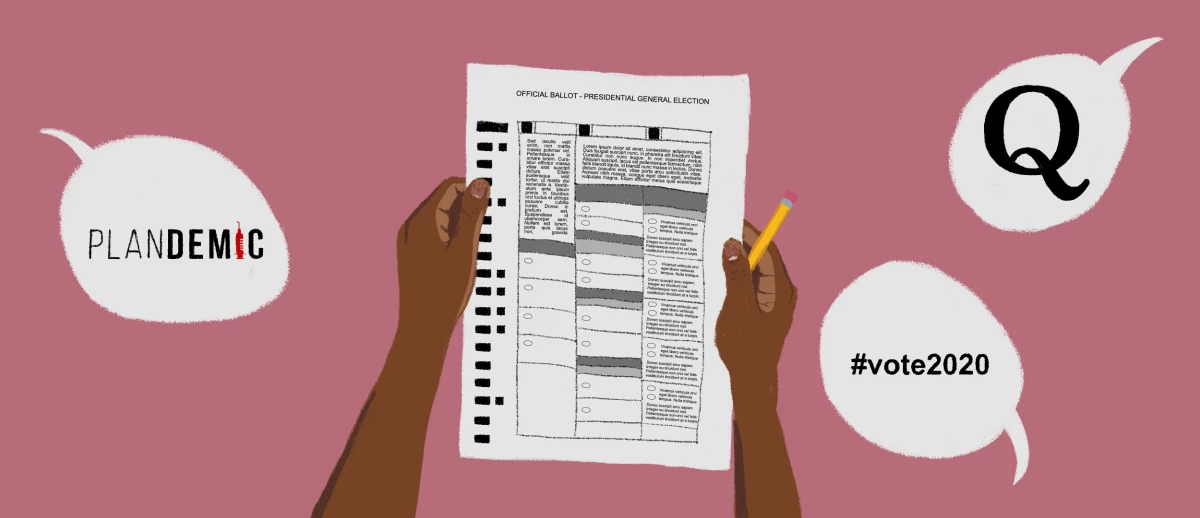

- Why We Desperately Need More Research on Social Media’s Effects on Democracy

Why We Desperately Need More Research on Social Media’s Effects on Democracy

A new book argues academic researchers should have more access to the data locked inside Facebook, Twitter, and other social media platforms.

Credit: Judy Zhang

Authors

Area of Study

Tags

The employees of the platforms are the only ones who really know the scale of the problems widely attributed to them.”

Nathaniel Persily and Joshua Tucker wrote that statement in their new book, which explores the field of social media research and brings a major limitation into sharp focus: Facebook, Google, Twitter, and other platforms are the sole keepers of data that academic and independent researchers need to investigate and understand how social media shapes democracy.

Persily is a professor at Stanford Law School and co-director of the university’s Cyber Policy Center, while Tucker is a professor of politics at NYU and co-director of its Center for Social Media and Politics. Together, they edited a volume that draws a straight line from the utopianism of the early internet — with its promises to build community and subvert antidemocratic forces around the world — to a post-2016 world, in which public discussion of the relationship between social media and politics is dominated by the spread of false news, foreign and domestic actors launching disinformation campaigns to target voters, and fringe conspiracy movements gaining traction online and propelling their devotees to victory in U.S. congressional primary races.

Titled Social Media and Democracy: The State of the Field and Prospects for Reform, the book was published by Cambridge University Press, is out via open access online, and will be available in hardcover and paperback on September 3. It includes chapters written by leading scholars of disinformation, hate speech, and political advertising among other topics. The final chapter was written by Persily and Tucker. It details the challenges researchers face in trying to access social media data, and the tremendous opportunities should “those of us on the outside” unlock that data, analyze it, and release our findings to policymakers and the broader public.

I reached out to Persily and Tucker via Zoom to discuss the book’s main points. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

Siriwardane:

Can you tell me what you’re trying to accomplish in this book?

Persily:

We’re of the view that much of the conventional wisdom about social media’s effects on democracy is not just wrong, but it’s also dangerous — especially when it affects policy. That’s because so much of that conventional wisdom is not informed by actual empirical research.

We thought it was important to combine research findings from social scientists who’ve been analyzing these problems with a discussion of major policy interventions around social media. We put it all in one place so that people who are interested in policy can be exposed to the research, while those who are focused on the empirical findings can understand some of the policy disagreements. There is no other book that does that.

Tucker:

One of the reviewers wanted us to split it into two volumes, but we were attracted to the idea of trying to get information that would be useful to those interested in both basic scientific research and questions of public policy.

The result was a book in which the first seven chapters look like they could have come out of the Annual Review of Political Science, while the latter chapters look like they could have come out of a policy briefing. We show how these policy debates are responding to things people think are happening on the internet, and on social media platforms in particular. But that first half of the book is where you can go to find out how much — and in many cases, how little — we actually know about the assumptions underlying those policy debates. That’s what ties everything together.

Much of the conventional wisdom about social media’s effects on democracy is not just wrong, but it’s also dangerous — especially when it affects policy.

Siriwardane:

You write in the book that Russian intervention during the 2016 U.S. presidential election was top of mind when you began assembling these chapters. But you also detail how the landscape shifted during the months leading up to publication. How do recent developments — such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the George Floyd protests — reframe both the scholarship and policy debates in the book?

Persily:

Think of public opinion on social media’s impact on democracy as a pendulum. It has swung wildly in the last five years — from irrational exuberance to apocalypticism. The swing of the pendulum is in response to particular events that are happening out in the world.

Tucker:

We’re not saying that foreign interference in the 2016 election is what made social media’s effects on democracy important. What we are saying is that after 2016, this euphoric period of viewing social media as liberation technology came to a crashing end. The pendulum then swings really far in the other direction, and the conventional wisdom becomes, “Social media is a threat to the United States and a threat to democracy itself.” At that point you get tremendous interest in the impact of social media from policymakers in democracies such as the United States, because social media is no longer just a potential tool of foreign policy — it now seems increasingly consequential for domestic politics as well.

This informs the three main threads of the book: The first thread is this demand after 2016 for policy around social media, whether it’s regulating hate speech or political ads, or breaking up the platforms. The second thread is that discussion becomes largely informed by the pundit class, who often rely on anecdotal evidence, partly because systematically analyzing social media data is really, really hard. It often requires large collaborative teams with the ability to collect, store, and analyze very large collections of data. The third thread is that all of sudden the data necessary to analyze what’s going on with social media is owned by these giant companies. That means the very platforms we need to study to try to understand some of the most pressing questions about our democracy also control access to much of the data needed to do so.

Persily and Tucker’s book is available via open access here.

Siriwardane:

The chapters in the book cover topics that range from hate speech to online propaganda to political advertising. Can you talk about how these diverse topics come together to paint a picture about the relationship between social media and democracy?

Persily:

We organized the book to represent the biggest problems people see in social media. So, it’s natural to start off with a chapter about misinformation because there is a lot of concern that this type of content on Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter is polluting the information ecosystem. And then we move toward political polarization with a chapter on echo chambers. From there we move on to hate speech, which is the most virulent form of polarization and a chief focus of proposed reforms for social media platforms. And then we take on the rise of online political advertising and social media’s impact on legacy media institutions. Conventional wisdom has strong opinions on all of these issues, but we actually provide the rigorous scientific evidence behind them.

Tucker:

If there’s one overlying theme, it’s that a lot of these chapters do push back on that conventional wisdom that Nate’s talking about, which you’d get from turning on cable news and watching people pontificate about the internet.

Siriwardane:

Let’s go back to the choice to include scientific analysis and policy discussion in one volume. You explain this by pointing out that the scientific and policy communities don’t talk to each other and share information enough. What are the consequences of these siloes?

Persily:

We’re concerned that public policy is being made without the benefit of rigorous scientific research. This isn’t the only area where that happens, but in this domain, you have a very fast-moving technology with serious questions about speech rights at stake. If policymakers are going to base decisions about hate speech and disinformation on just anecdotes, they are going to get it wrong and might even make things worse.

Tucker:

I do think it’s a supply-side problem. If the scientific research community doesn’t make its work accessible, there are lots of other people who are willing to step into the void and tell policymakers what they should be doing about the social media platforms.

I also want to note the importance of academic researchers in solving this problem. Academics are particularly valuable here because we are rewarded for putting what we’ve learned into the public domain. That’s the nature of our profession. There are plenty of good reasons to support making social media data available to potential economic competitors of the platforms, as well as to NGOs and civil society groups, but these actors can accomplish their goals without sharing what they’ve learned from their data analysis with the public. Conversely, the currency of academia is publishing, or putting what we’ve learned into the public domain. That’s why we keep making such a forceful case for making more social media data available to academic researchers.

The only people who are analyzing the data — and gaining all the scientific insights from studying it — are employees of the platforms. It means the single greatest dataset ever compiled for understanding human behavior is, in the short term, going to be used to maximize the profits of Google and Facebook.

Siriwardane:

Let’s discuss the final chapter, which advocates for policies that support and encourage that kind of access to social media data. Why are these policies so important and how can they help the public gain answers to what happened in 2016 and what could happen in the future?

Persily:

When it comes to social media research, it’s the best of times and it’s the worst of times. There is more data available that could potentially answer the most significant social questions of the day. But most of that data is locked up in private companies and not available to most social scientists. The challenge for social science right now is to try to find a way to analyze that proprietary data in a way that protects the privacy of individuals and answers these big social questions.

Tucker:

We come up with a three-part approach in the final chapter to do this. One: Cooperate with the platforms when they’re willing to share data and make sure that they will not have a right of refusal over what you’re going to publish. Two: Work around the platforms whenever you can. Scholars are finding all sorts of innovative ways to do this, like asking people to install browsers that let us actually look at what YouTube algorithms recommend. And three: The legal barriers to access to this data are a result of current laws. So try to get governments to step in and change these laws.

Siriwardane:

Can you talk about some of the ethical challenges around analyzing social media data once you gain access to it?

Persily:

The main ethical challenge stems from the fact that people have an expectation of privacy — that most of their interactions online will not be made public. And so we need to make sure that we develop procedures and technology that protect the identity of respondents. We also need to integrate the privacy community into the larger discussions that academics are having with the platforms.

Tucker:

The idea of privacy online is so normatively pleasing that we all agree with it. I think a lot of people make the leap from “online privacy is good” — which it is — to “social media data should never be shared with anybody outside the platforms.” But what gets lost here is the fact that this doesn’t mean that people’s data and behaviors on the platforms aren’t being analyzed. What it means is that the only people who are analyzing the data — and gaining all the scientific insights from studying it — are employees of the platforms. It means the single greatest dataset ever compiled for understanding human behavior is, in the short term, going to be used to maximize the profits of Google and Facebook. And in the long term, it’s going to be used to do whatever Google and Facebook decide they want to do with that.

That’s why we need to begin to think about the tradeoffs between two competing “goods”: protecting people’s online privacy, and ensuring the vast amounts of data being collected by a small number of giant corporations can be used to benefit society, as opposed to just those corporations.

Venuri Siriwardane is the Researcher/Editor at the Center for Social Media and Politics. She holds a master’s degree in Politics and Communication from the London School of Economics, where her research interests included political legitimacy in postcolonial states. In a previous life, she worked as a business journalist in New York.

This piece was originally published on August 29, 2020.

Read the Original Medium Post Here.