Who Was Most Likely to Share Fake News in 2016? Seniors.

In general, people don't tend to share a lot of links to fake news websites, but those that do are more likely to be older and more politically conservative.

Credit: Pexels

Authors

Area of Study

Tags

This article was originally published at The Washington Post.

This week, the New York Times broke the news that Democratic activists posted misleading Facebook pages and Twitter feeds during the 2017 U.S. Senate race in Alabama. That’s just the latest iteration in the ongoing saga of online disinformation and “fake news” since the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Researchers have learned a lot about fake news — who produced the content, who encountered it, who may have believed it and how to counteract it.

Now we know a bit more about who actually shared it. In research we are publishing today in the journal Science Advances, we find that in general, the proportion of people on Facebook who shared links to fake news websites was relatively low. That said, however, older Americans — especially those over 65 — were much more likely to share fake news than younger ones, and conservatives and Republicans were more likely to share fake news than were liberals and Democrats.

How we did our research

With support from the National Science Foundation, the Social Media and Political Participation (SMaPP) Lab at New York University commissioned a panel survey during the 2016 U.S. election campaign. After the election, respondents were asked whether they were willing to share information about their available timeline posts on Facebook, including external links they had posted on their profiles.

About 1,300 respondents agreed to share this information using a Facebook app developed by the SMaPP Lab and approved by Facebook for research purposes. Because these respondents had previously answered our survey questions, we also had data on their age, ideology, self-reported partisan identification, and so on. Those who agreed to share were somewhat more Democratic (40 percent vs. 32 percent) than the full population of those who reported having a Facebook account, but they were very similar to those who did not share in terms of age, education and likelihood of casting a vote.

We then compared links shared by the respondents to several lists of Internet domains known to be purveyors of “fake news,” relying mainly on a list compiled by Craig Silverman at BuzzFeed News. But we also checked for sites listed by other peer-reviewed research, those listed on a crowdsourced effort to compile dubious information sources and those among a list of specifically debunked articles.

Not that many people shared fake news

According to our data, fewer than 1 in 10, or 8.5 percent, of our respondents shared links from fake news domains. (For comparison, about 1 in 4 Americans during the last weeks of the 2016 campaign read or clicked on at least one fake news article, regardless of how they encountered it.)

Most people who did share links to articles on fake news domains did not share many of them. But, like many patterns of online behavior, we observe a “long tail” of a relatively small number of people who shared a disproportionate number of links. (In our entire sample, only 13 people shared more than five links to a fake news site.) Of course, each shared link may have been viewed by many people, although we can’t say for sure from our data.

The best predictor of sharing fake news? Being over age 65.

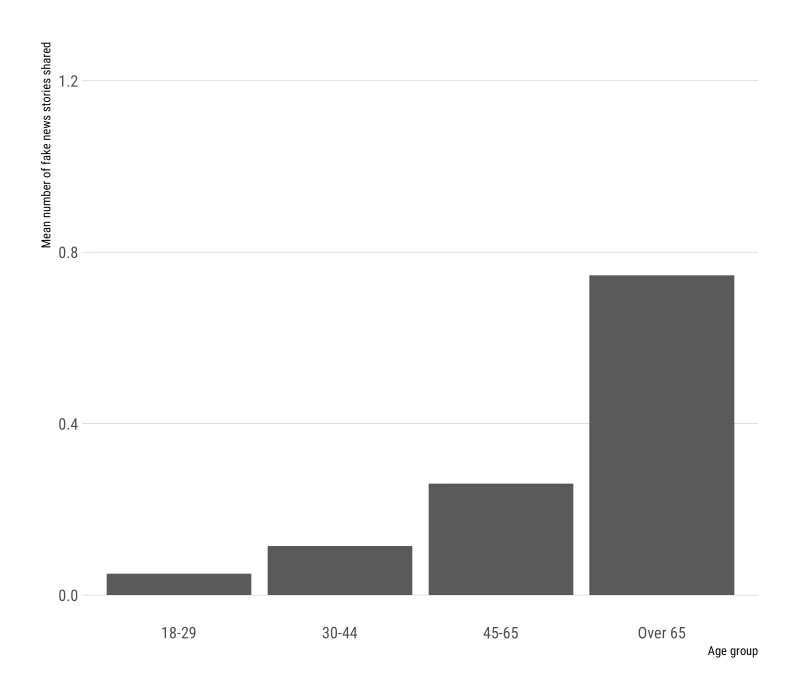

In the figure below, you can see immediately which age group was most likely to share links to fake news.

More than 1 in 10, or 11.3 percent, of people over age 65 shared links from a fake news site, while only 3 percent of those age 18 to 29 did so. These gaps between old and young hold up even after controlling for partisanship and ideology. No other demographic characteristic we examined — gender, income, education — had any consistent relationship with the likelihood of sharing fake news. Our results are also not driven by overall tendencies to just generally share links on Facebook.

In a study like this, we can’t distinguish between age and birth cohort. We don’t know whether “being old” is associated with sharing more fake news, or if it’s being in the generation born before 1950. In other words, we do not know whether people raised in the modern digital environment — digital natives — will share more fake news as they age. What’s more, age may be a proxy here for other factors, such as digital media literacy.

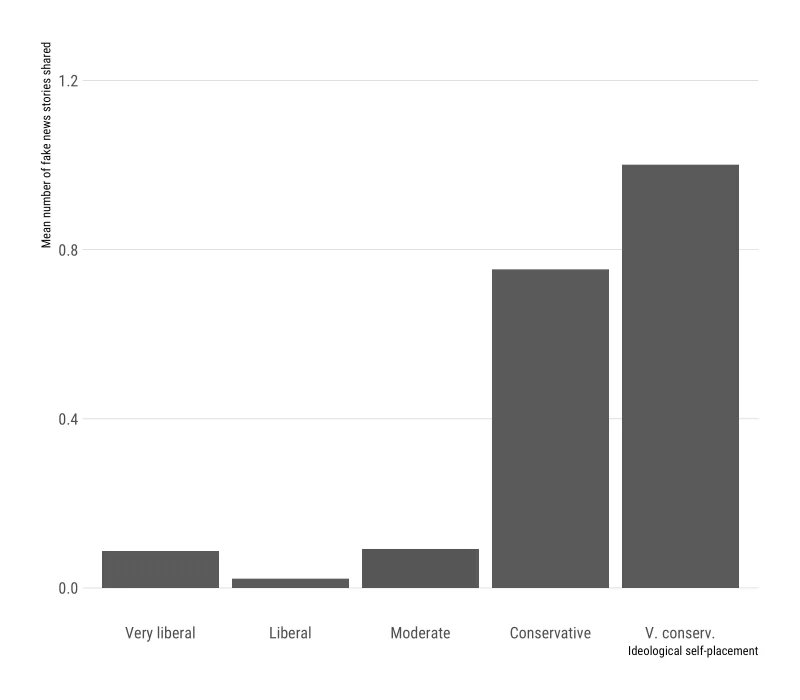

Conservatives and Republicans shared more fake news than Democrats and liberals

While 18 percent of Republicans in our sample shared links from fake news sites, only 3.5 percent of Democrats did. And as the figure below shows, self-identified conservatives on average shared more links to fake news stories than moderates or liberals.

We don’t know why this is. Conservatives may have shared more fake news stories than liberals because most fake news sites offered pro-Trump or anti-Clinton content, aimed specifically at Republicans and conservatives. Had the slant of fake news been pro-Clinton instead of pro-Trump, it is possible that more liberals than conservatives would have shared this content.

Interestingly, these findings may relate more directly to ideology than to partisanship: Self-identified independents were about as likely as Republicans to share links from fake news domains — although self-identified Democrats were much less likely to do so than either independents or Republicans.

So what’s next?

Our results focus on social media behavior from over two years ago. Online, that’s virtually an eternity. Much has probably changed since then.

For one thing, Facebook has engaged in numerous efforts to counteract the spread of online misinformation. Possibly as a result, independent research has found noticeable declines in the prevalence of this content on Facebook since then. Either way, there’s more to be done to determine whether the patterns we identified in 2016 continue to describe the sharing of fake news in 2019 in the United States and elsewhere.

Andy Guess (@andyguess) is an assistant professor of politics and public affairs at Princeton University.

Jonathan Nagler (@Jonathan_Nagler) is a professor in the Wilf Family Department of Politics and a co-director of the Social Media and Political Participation Lab at NYU.